Lab-made rare blood gives hope to patients

Our scientists are getting closer to tailor-made red cells

Regular blood transfusion is the cornerstone of care for patients with red blood cell (RBC) disorders such as thalassaemia or sickle cell disease. With repeated transfusions, however, there is a heightened risk of alloimmunisation (that is, patients’ immune systems starting to recognise the transfused cells as foreign and making antibodies against proteins on the surface of the transfused red cells).

Regular blood transfusion is the cornerstone of care for patients with red blood cell (RBC) disorders such as thalassaemia or sickle cell disease. With repeated transfusions, however, there is a heightened risk of alloimmunisation (that is, patients’ immune systems starting to recognise the transfused cells as foreign and making antibodies against proteins on the surface of the transfused red cells).

The matching that we carry out between donors and patients reduces this risk, but patients who receive multiple transfusions need blood that’s more closely matched. You can read more at ‘Why we need more black blood donors'.

Patients with rare blood types also face an enormous challenge when it comes to finding matching donors. These donors must either have, or lack, the specific antigens required for a successful transfusion. Read more about the importance of specially matched blood. In some cases there may only be a handful of suitably matched donors in the country.

Designer red cells

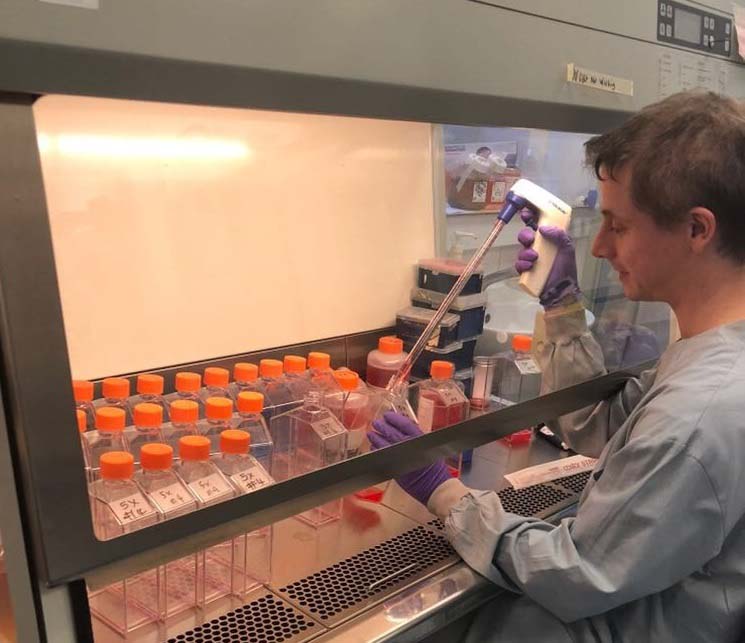

With this in mind, our scientists have been working with the University of Bristol to create cell lines that produce red cells with rare blood types, a step towards treating patients who currently can’t be closely matched with donor blood.

Using new techniques in gene editing, our scientists have been able to make red cell lines in which specific blood group genes have been altered. This has allowed them to produce cells with could be used in a wide range of transfusions and potentially offer fresh hope to future generations of patients whose clinical needs are difficult to meet.

More work needed

Dr Ashley Toye, the Director of the National Institute for Health Research Blood and Transplant Research Unit says, “Blood made using genetically edited cells could one day provide compatible transfusions for a group of patients for whom blood matching is difficult or impossible to achieve within the donor population. However, much more work will still be needed to produce blood cells suitable for patient use.”